Finding the Villas

When, in 1852, the Crystal Palace was moved to its new permanent site on the heights of Upper Sydenham, it fired the starting gun for a race to develop the area. The ridge running northwards from the site, with its fine views over Kent to the east and London to the north, its clean air and wooded character, attracted developers who saw it as an ideal spot to build large villas for the wealthy. The area had already attracted interest for development and in 1851, Beltwood was built for a London solicitor, Edward Saxton and his family. This house and much of its grounds remain and are not part of the Wood.

|

Beltwood House in 1916

|

|

Beltwood House photographed in 1953

|

A brief history of the villas in the Wood.

|

| A composite of two OS maps from 1870 showing the main villas on the west side of Sydenham Hill. |

|

Much

of the land was owned by the Dulwich Estate, so the new mansions and

their extensive grounds were sold subject to 99 year leases. By the

1860's, the large mansions had been completed and this remnant of the

Great North Wood altered beyond recognition by lawns, winding paths,

large greenhouse and even a folly. At the start, the new villas

attracted the wealthy and famous. In 1865 a new railway was built from Nunhead to the new Crystal Palace High Level station and it was this line that cut its way through the land which now forms Sydenham and Dulwich Woods. The new villas were thus connected to central London by three stations, Sydenham Hill with trains to Victoria, or Upper Sydenham and Lordship Lane connecting wealthy residents to the City at Blackfriars. However, having a new railway at the bottom of the garden was not what the very wealthy desired so woodland was planted close to the line to act as a barrier between it and the villas. The Palace never fulfilled the hopes of its backers and by the latter years of the Nineteenth Century it was in terminal decline. Except for excursion trains, the railway became a backwater and the villas followed both Palace and railway into a slow decline.

Lapsewood,

built in 1860, was the home of Charles Barry Jnr, the architect of Dulwich College's New

Building and was responsible for the initial designs of Dulwich Park. In the 1870s he sold the lease to Edward Clarke, a wealthy stockbroker who lived there until his death in 1916. His wife carried on living there until her death in 1928. However, as the lease had a short period left to run, the executors found it difficult to sell the house until, in 1931 the Government acquired it. Consequently it became a training centre for domestic servants as part of an unemployment relief scheme, the trainees being taken from the areas of worst unemployment. Presumably the war put an end to this and in 1947 it was re-let as a hostel for student teachers, then in the 1950s it was sub-divided into flats. It was demolished sometime in the early 1970s.

|

Lapsewood House, date unknown but likely early C20.

|

Next door was Beechgrove, built about 1862, the first resident being an East India merchant, William Patterson, who

lived there until his death in 1898. The house would see a succession of

residents. From 1932 to 1947 was home to Lionel Logue, the speech

therapist of the future King George 6th. It is a sign of things to come

that Lionel Logue found the house increasingly expensive to maintain, especially during the war and it is said that he had a sheep to keep the lawns under control. His wife died in 1945 and, in 1947, he moved to a flat in Knightsbridge, The house remained vacant until 1952

when it became The Red Cross Home for Aged Sick. This closed sometime in the late '70s, remaining empty until its demolition in 1983. It was thus the last remaining villa to be demolished.

It grounds remained fenced off and were only incorporated into Sydenham Hill Wood in 2016. For a while in the late 1990s into the early 2000s it was home to Soloman, who lived in a hut built onto the the cellar ruins of the house, growing his own vegetable in the grounds. Eventually, he moved into sheltered accommodation but the wall he painted is still testament to this remarkable man.

|

| This 1905 view shows the main entrance which faced west with view across the extensive grounds and to London beyond. Sydenham Hill ran behind the house. |

|

|

A slightly later view of the house taken from its gardens, the sundial marked as SD on the map can be seen in the bottom right hand corner. This is not evident on a 1916 version of the map.

|

Next to Beechgrove was Fairwood, which was built around 1864 and is notable for the folly built in its garden. Its first resident was Alderman David Henry Stone, later to be Lord Mayor of London and it was he who commissioned the James Pulham & Co to build a ruined chapel and adjacent cascade from artificial rock, Pulhamite. Sadly, there seem to exist no known drawings or later photos of the folly, except for those taken recently. Oddly, a contemporary Pulhamite catalogue listed the folly as being in the grounds of The Hoo, although this would seem to be incorrect. It is thought that when built, the arch of the folly would have been complete and it is said that until the 1950s, stained glass could still be seen in the windows, although no sign of this exists now.

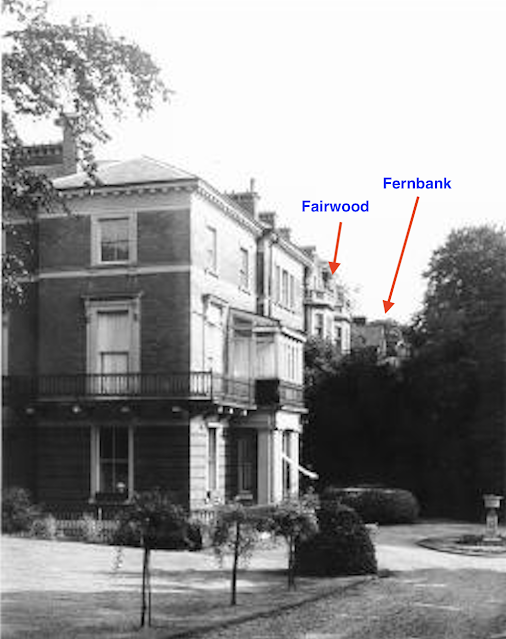

Although few photos seem to be available of Fairwood, the image below of Beechgrove between the wars, shows both Fairwood and beyond that Fernbank peeping out of the trees. Closer examination of what can be seen suggests that the bay windows, topped with parapets and the ornate gables match the drawing below for a villa on Sydenham Hill and suggests that this is very likely to be the architects drawing for Fairwood.

This photo has come to light from the sales information when the house was being sold in 1908

Sadly, there seems to be no information available about the next house which was called Fernbank, although early maps show an elaborate garden with formal terraces near to the house, giving way to paths meandering through woodland further down slope.

Next to the south was The Hoo, which according to taste was either the most spectacular house or the biggest monstrosity along this stretch of Sydenham Hill.

These two engravings from 1875 show the house from the front and then the rear garden.

It is said that the small conifer seen in the right middle ground of the engraving is the Cedar of Lebanon when young. otherwise, nothing remains of The Hoo save for some decorative corbels lying on the ground. The large hollow in front of the cedar is said to be an impact crater from an unexploded WW2 bomb, although the 1870 OS map below shows a circular hollow as part of the terraced gardens, which would be in roughly the same place.

|

| A photo of The Hoo in 1906 |

To the south of The Hoo, the two remaining houses were called Bardowie and Oakover. The remains of the terrace in Bardowie's rear garden are still extant and steps lead down to what is now called the tennis-court glade. In the photo below, Blairdowie is seen to the right of the horse and cart. The cart obscures the turning into Crescent Wood Rd. The house beyond is now the site of Countisbury House, which was built around 1957.

Of Oakover, nothing remains, although the monkey puzzle tree which can be seen to the east of the path down to the tunnel, is a remnant of its garden. It would seem that there are no photos or drawing of either of these houses.

Although not within the boundary of the Wood, the house next to Oakover in Crescent Wood Road was a modest affair in comparison and had the smallest garden, as it was limited by the railway owned land above the tunnel mouth. It was located where the Crescent Wood entrance to the Wood meets the entrance to Peckarman's Wood estate.

|

Ashmore, 21 Crescent Wood Rd.

|

The photo below shows the north portal of the Crescent Wood Tunnel. Although the line closed in 1954, it took until 1957 to remove all the tracks. To the left, the shape of Countisbury House can be seen beyond the trees and Ashmore can be seen just above the left hand side of the tunnel mouth.

The next post will look at what remains of the villas can be found hidden in the Wood.

Comments

Post a Comment